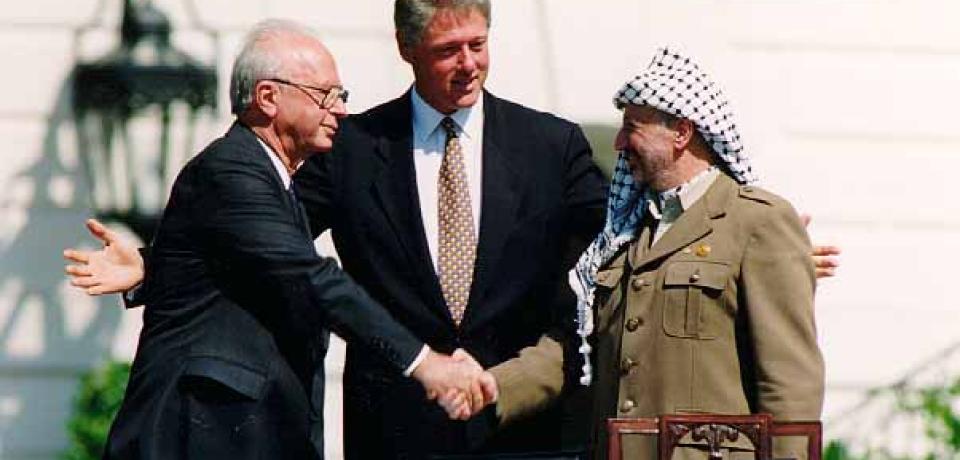

The Oslo Accords were a historic event. But nearly thirty years on, no one uses them to talk about the situation in Palestine. There is no longer any talk of the “peace process” or the “quartet”, as was the norm in the 1990s and 2000s, so far have things moved away from the hopes raised by these agreements.

The agreements of 13 September 1993 signed by the Israeli state and the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were intended to bring about a lasting solution to the “conflict” and enable the creation of a Palestinian state, a historic demand of the national liberation movement. The agreements provided for the gradual transfer of the West Bank territories under the control of a newly-created Palestinian authority.

This transfer was to take place via a division of the West Bank territories into three zones: zones A, B and C for a transition period of five years. This division endorsed an Israeli demand for differentiated management of these zones. The territories in Area A (18% of the total surface area of the territories) were essentially the major Palestinian towns (except Hebron), where most of the population was concentrated, to be under Palestinian civil and military control. Area B, approximately a quarter of the territory, comprised the Palestinian villages, under Palestinian civilian and Israeli military control. The remaining 60% of the territory (Area C) was the only unfragmented strip of land, entirely under Israeli control. It includes the Israeli settlements in the West Bank, Gaza (dismantled since 2005) and East Jerusalem, which is under Israeli military control.

No real autonomy for the Palestinians

Nearly thirty years on, the situation in these temporary zones has changed little, while the number of settlements (in Area C) has exploded: on average, almost 14,000 settlers move into the occupied territories every year. There will be 460,000 settlers in 2021, compared with 110,000 at the time of the Oslo Accords.1 The agreements were never a contract between two equal partners. It was an agreement imposed by an occupier on an occupied party with little negotiating power. In addition, the texts were vague, ambiguous and favourable to Israel. For example, they made no provision for halting the colonisation of land that was supposed to be returned to the Palestinians. Israel therefore continued to develop the settlements after the agreements were signed.2

Even if they had been carried out as planned, the Oslo Accords effectively created a Palestine with 10% of its historic territory divided between Gaza and the West Bank and a “state” under permanent trusteeship with no real autonomy for the Palestinians. The Palestinian people would have continued to be divided between the people of the West Bank, the people of 1948 and, of course, the refugees.

Reorganization of the occupation apparatus

The Oslo process would not have led to the satisfaction of the Palestinians’ national rights. The Palestinian leadership found itself de facto put forward by the occupier and structurally integrated into the architecture of the occupation. From the outset, these agreements and this “peace process” have served as a support for a reorganization of the system of occupation of the Palestinian territories, anticipated for a long time by part of the Israeli ruling class.

The Oslo architecture actually enabled the Israeli authorities to resolve the paradox that had confronted them since the June 1967 war, at the end of which the State of Israel occupied the whole of Palestine, theoretically partitioned in 1947-1948. [...] The military success thus created a political difficulty: Israel was now home to the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza, in addition to the Palestinians of 1948. The State of Israel”s claim to be simultaneously a “Jewish State” and a “democratic State” is therefore seriously threatened.3

It is in this light that the Israeli strategy and the dynamic behind the “areas” must be understood: giving up sovereignty over the most densely populated Palestinian areas while retaining control over the Jordan Valley, the shores of the Dead Sea and Jerusalem, whose municipal boundaries would be extended. The layout of the settlements, the roads reserved for settlers and the fragmentation of the West Bank were a concrete application of this angle. So this was not a historic compromise on the Israeli side. The Oslo Accords were an adaptation of the Zionist project to the realities on the ground: the 1987 Intifada exposed the situation of the Palestinians in the occupied territories, helping to delegitimize the State of Israel and threatening to destabilize the Middle East.

Israel’s non-acceptance of the Palestinian state

In April 1994, the agreements that followed the Oslo declaration resulted in the Paris agreements defining the economic relations between the Palestinian “controlled” areas and the State of Israel. The Palestinian economy came under Israeli control, with restrictions on imports and the setting of tax levels. In 1995, the Taba agreements, also known as Oslo II, set out the conditions for the transfer of occupied areas to the Palestinians (Areas A and B) on the ultimate condition that the new Palestinian institution ensure the occupier’s security, i.e. suppress Palestinian resistance to the occupation. From the Oslo declaration to the present day, the many “negotiations” or “peace” plans that have followed - Camp David in 2000, the Quartet in 2002, Anapolis in 2007 - have all come up against the Israeli determination not to accept the existence of an independent Palestinian state on part of the land of historic Palestine under this security pretext.

As well as corresponding to the views of the Israeli state, Oslo placed Israel’s colonization of the Palestinians in the context of a symmetrical conflict between antagonistic states. The slightest act of violence has its “symmetrical” counterpart on one side, without measuring the glaring disparity in the victims, destruction, etc., of the other. Oslo made it possible to develop a rhetoric of permanent temporary existence, because the other party - the Palestinians - did not play the game of agreements that were unfavourable to them. The slightest pretext was used to crack down harder and to colonize even more in the name of the “peace process”. The constraints imposed on Israel by Oslo were always dependent on a situation that had to be assessed by Israel itself, particularly in terms of security.

This symmetry of the conflict - non-existent from the point of view of political and military influence - was used by Israel to ensure a benevolent neutrality both politically and in the media.

Israel, an apartheid state

For the last ten years or so, no serious actor has been talking about the peace process again, or putting forward the roadmap that emerged from the Oslo Accords. In fact, from this point of view, it is a complete reversal: the international community continues to feed the charade of symmetry between the two sides, while the Israeli state is becoming increasingly radicalized.

In 2018, the Israeli Parliament passed a new Basic Law, entitled “Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People”, Article 1 of which states: “The exercise of the right to national self-determination in the State of Israel is reserved for the Jewish people”, a right therefore denied to the Palestinians; another article stipulates that "the State considers the development of Jewish settlement as a national objective and will act to encourage and promote its initiatives and its strengthening” - which means the right to confiscate land, belonging to Palestinians. Above all, this text normalises a practice that for decades has turned Israel into an apartheid state. In 2021, the Israeli organisation B'Tselem concluded that “a regime of Jewish supremacy exists between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean”. It was followed by two major international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.4

However, despite the de facto support of the USA and Europe, Israel’s image is increasingly tarnished: the fierce resistance of the Palestinians has ensured that their situation is still discussed at international level and that regular actions take place at the level of the United Nations and other working groups linked to the UN organisation, despite the systematic American veto.

Through the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) solidarity campaign propelled by Palestinian civil society, Israel’s image of normality has been shattered and, although few in number, the symbolic victories of boycott and divestment have borne fruit and led to debate on the struggle of Palestinians and the injustice they experience on a daily basis in occupied Palestine. The fascization of Israeli society and the resistance it arouses in Israeli civil society must not mask the extent of colonisation and the fate of Palestinians under occupation.

Thirty years on, the hopes raised by the Oslo Accords have been dashed. They point the way to what must not be done. There can be no “peace process” under occupation and colonization.

9 September 2023

Translated by International Viewpoint from l’Anticapitaliste.

Édouard Soulier is a member of the Nouveau parti anticapitaliste

- 1Le Monde, 31 July 2023, “Cinquante ans d’occupation illégale en Cisjordanie : comment la colonisation n’a cessé de s’étendre” https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2023/07/31/cinquante-ans-d-occupation-illegale-en-cisjordanie-comment-la-colonisation-n-a-cesse-de-s-etendre_5386842_4355771.html

- 2Le Monde Diplomatique, 22 October 2007 “Pourquoi les accords d’Oslo ont-ils échoué ?” https://blog.mondediplo.net/2007-10-22-Pourquoi-les-accords-d-Oslo-ont-ils-echoue

- 3Mediapart, 12 September 2013 “Oslo, 20 ans après : il n’y a jamais eu de processus de paix ” https://blogs.mediapart.fr/edition/les-invites-de-mediapart/article/120913/oslo-20-ans-apres-il-n-y-jamais-eu-de-processus-de-paix

- 4Le Monde Diplomatique, September 2022 ”De la colonisation à l’apartheid” https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2022/09/GRESH/65084