On the island of Mindanao, in the south of the Philippine archipelago, the creation in 2019 of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was a particularly significant event in the country’s history. It marked the end of decades of conflict over recognition of the right to self-determination of a population that had long been discriminated against and oppressed.

However, BARMM is also inhabited by Christian populations from the north and center of the archipelago, as well as by the Lumad1, i.e. indigenous peoples from Mindanao, with diverse religious beliefs, but sharing the same way of life, attached to the forest. These are the Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples (NMIPs).

The Lumad’s ancestral domains lie alongside, or within, territories claimed by various Moro clans. During the long liberation struggle waged, often in military form, by Muslim movements, the Lumad demanded that the demarcation of their ancestral territories be formalized by mutual agreement with their neighbors, and recognized by local, regional and national authorities.

This was finally achieved at national level, but not at regional level, and the two levels of responsibility collided.

No Indigenous Peoples’ Code

The rights of the indigenous peoples in the north of the archipelago, notably the Igorots, had already been formally recognized by the national authorities, but it took a great deal of mobilization on the part of the Lumad, who came to Manila in delegations, and the Filipino movements that supported them, for their existence to be effectively taken into account. The “Muslim question” monopolized attention - at the height of the fighting, two-thirds of the Philippine armed forces were sent to this theater of operations. Most of the organizations defending the Lumad (who were also often victims of the army) ran joint solidarity campaigns for indigenous peoples and Muslim populations. They campaigned in central and southern Mindanao to build active solidarity between the “three peoples of Mindanao”.

The experience is bitter: the Lumad are today denied the recognition of their rights that they were on the verge of finally obtaining.

When the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) was entrenched, it’s tasked to create the new autonomous regions institutions and drafting key legislations or priority codes, one of which is the Indigenous Peoples Code. However, while it’s term has already extended, this key legislation is still not passed until the present. Instead, the BTA created the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples Affairs (MIPA) which do not recognize the Indigenous Political Structures (IPS) of the Teduray and Lambangian, instead it organized tribal councils, which not only delegitimizes the existing IPS but also caused confusion and division in the NMIP communities2.

The Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) 1st Parliament issued Resolution No. 38 urging the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples to CEASE and DESIST the delineation process and issuance of Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) for the Tëduray and Lambangian in Maguindanao province in September 25, 2019. This to the NMIPs is a denial of their right to the protection of their Fusaka Ingëd(ancestral domain) and hindered their full participation in decision making in terms of formulating comprehensive land use plans, programs and activities allowed by law within their claimed territory3.

In fact, their situation is once again tending to worsen, as highlighted in a June 23, 2023 report to the Commission on Human Rights4 to which Tata, who has been involved with the Lumad for many years, refers. This report was prepared by the Timuay Justice and Governance and the Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center. It stated that …”the NMIPs continue to face conflict and violence rooted in the continuing land disputes within their ancestral domains. Since 2018, they have recorded a total of 55 killings among NMIPs. The cases affecting 41 of these victims remain unresolved. Furthermore, they have documented 10 incidents of displacements of at least 3,468 NMIP families from 2020 to 2022, caused by harassments from recognized battalions of Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF) and different local armed groups, and operations of the Philippine military. While most of the internally displaced persons (IDP) were able to return to their homes, recovery and rehabilitation has yet to be provided by public authorities. Individuals who have been forced to go into hiding due to threats to their life are not included in this report. These threats are present because they have called attention to the violations committed against their communities. They remain at risk and without a secure sanctuary.”

To the previous factors of conflict, new ones have been added, and in a major way. The BARMM authorities have adopted as their development model the promotion of commercial tourism, extractivism (mining and oil resources) and large-scale forest exploitation5. The Lumad’s ancestral domains are thus the object of the covetousness of powerful economic interests. This is not a new issue, but this time Moro businessmen are getting involved by enlisting the support of local and regional authorities.

Indigenous peoples, Moro clans: the Barangay Biarong, a textbook case

Barangay6 Biarong is located in South Upi, in the Maguindanao del Sur region, itself part of BARMM. The Lumad Tëduray and Lambangian indigenous peoples inhabited this area long before the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in 2019. They remain the majority in the area to this day.

Timuay Justice and Governance (TJG) speaks on their behalf7. On August 21, it published a statement that sounded the alarm about the situation in certain villages in the barangay Biarong8. The Maguindanaon9 moro clan from Talayan has moved in and intends to secure its power by being elected head of the barangay in the October elections.

The TJG noted in its statement that these territories “were once a peaceful place of the Tëduray and Lambangian where life is abundant and easy because of the fertile land area. These people were free to pactice their culture, tribal self-governance, language, system of worship and livelihood system. (...). The early leaderships of Barangay Biarong were held by the Tëduray, but lately, it was held by the Maguindanaon, despite of being minority in the place, but because they are empowed by the power of guns and goons they have had.”

The situation is made all the more volatile by the fact that two leaders of this Moro clan each aspire to take control of the Barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan (Youth Council) in the nationwide elections scheduled for October 30. Each has its own armed groups, and their confrontation has taken a violent turn. Non-Moro populations fear being caught in the crossfire. The Tëduray and Lambangian have taken refuge in an adjacent barangay, Lamud, or in the center of Barangay Biarong. However, the head of the local executive in South Upi ordered them to return to their homes.

In fact, many Lumad families wanted to return home, as they needed to harvest the rice, but they were asking for guarantees concerning their safety. Thus, the TJG “urged” all relevant local, regional and national authorities “to intervene in the sad situation of the non-moro Tëduray and Lambangian indigenous peoples in the region”.

What makes this conflict so special is that it pits two strongmen from the same clan against each other, but conflicts between Moro clans are commonplace. In the Philippines, dynastic “big families” traditionally consolidate their economic power and political influence by securing control of regional power structures, and every election gives rise to sometimes deadly settling of scores. This is even truer of the Moro clans, whose economic base is weaker, even if they do have their share of billionaires. “Electoral assassinations" between Moro clans can reach heights unknown in the rest of the archipelago.

Now that they have power with the autonomous region and are adopting a “development model” similar to that which prevails in the archipelago as a whole or in the non-Moro regions of Mindanao, it is possible that with the expansion of the tourism, mining, oil and forestry industries, the economic roots of the Moro clans will strengthen qualitatively. In any case, the enrichment of the Moro social elite will inevitably be at the expense of the Lumad.

Using the same vocabulary (ancestral domains) to address the claims of the Lumad and Moro clans is misleading. The latter operate in developed class societies where social inequalities are very great. The forest-people Lumad have nothing of the sort.

In addition, the various Moro movements are heavily armed, and their status has changed with the creation of BARMM, being in the process of being officially integrated into the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). The rich Moro families certainly keep their militias or private armies, but this is also true in other parts of the archipelago. The indigenous peoples we’re talking about here have set up self-defence forces in their territories to protect themselves from their enemies - of which there are unfortunately many - but there’s no comparison when it comes to the armaments at stake.

Mindanao is the scene of multiple armed conflicts of a very varied nature. Some can be settled through local negotiation. Citizens’ movements are helping to implement such peace processes. This is not the case with other conflicts, when the aggressors have major economic ambitions, or military aims (the takeover of strategically important ridges, for example).

Remembering the tragedy of Typhoon Paeng

From October 27 to 29, 2022, Typhoon Paeng (internationally known as Nalgae) hit the Philippines, primarily Mindanao (Maguindanao, Cotabato City, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato...), affecting almost a million people. The Tëduray, Lambangian and Mënubo Dulangan populations we’re talking about here have been hit hard: 1,730 families affected, 46 dead and 5 missing. Once again, the failure to recognize the rights of these indigenous peoples contributed to the tragedy.

As early as 1996, these indigenous peoples had demanded that the relevant authorities issue a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) - to no avail. This demand was reiterated within the framework of the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA), under the aegis of the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples (NCIP). It took 17 years before, on September 2, 2019, its investigation reports were submitted to the Ancestral Domains Office in Manila for review and approval.

As we already mentioned, the First Parliament of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) demanded that the Commission cease the process of demarcating the ancestral domains of the Tëduray, Lambangian and Mënubo Dulangan in Maguindanao province, and desist itself from the case. These indigenous peoples have then maintained their legal action, detailing their customary rights and claims. They asked the BTA to pass a resolution (which was not adopted) “Institutionalizing, Promoting, and Supporting Indigenous Peoples Forest Guards within the Ancestral Domain Areas” with the propose activities such as but not limited to the following: conduct forest protection; monitoring surveillance and law enforcement activities in coordination with proper law enforcement agencies and LGUs; coordinate and attend to Sanggunian Bayan and Barangay Council meetings on forest protection concerns with their area of assignment; conduct survey of forest occupants with their assigned areas; participate in meetings, activity assessment and planning sessions with DENR Officers and Staffs and other partners xxx.”

They also called for clarification of the areas of authority between the national level (NCIP), which prepared development plans for them, and the regional level (MIPA), which blocked procedures. They also called for BARMM to ensure the full participation of indigenous peoples’ own governance structures and organizations. This was not done. Local authorities have forced many families to move to the foot of Mt. Minandar, where the risk of flooding and landslides was high.10

For Sonia, with whom I was able to discuss these events, "the beach had to be cleared to ensure its development as a tourist attraction. Never mind the safety of the local population. They’re just Lumad”.

As their rights had not been recognized, the Lumads had no legal means of protecting themselves.

Redrawing Administrative Boundaries in 2022

On September 17, 2022, a new division of the province of Maguindanao was adopted by plebiscite. Politicians in favor of dividing the province argued that it would give citizens better access to basic social services such as education, health and transport with two provincial governments instead of one11. The initiative was supported by the United Bangsamoro Justice Party (UBJP), the political party of the Moro Islamic Liberation (MILF), who believe it will bring the government closer to the people12.

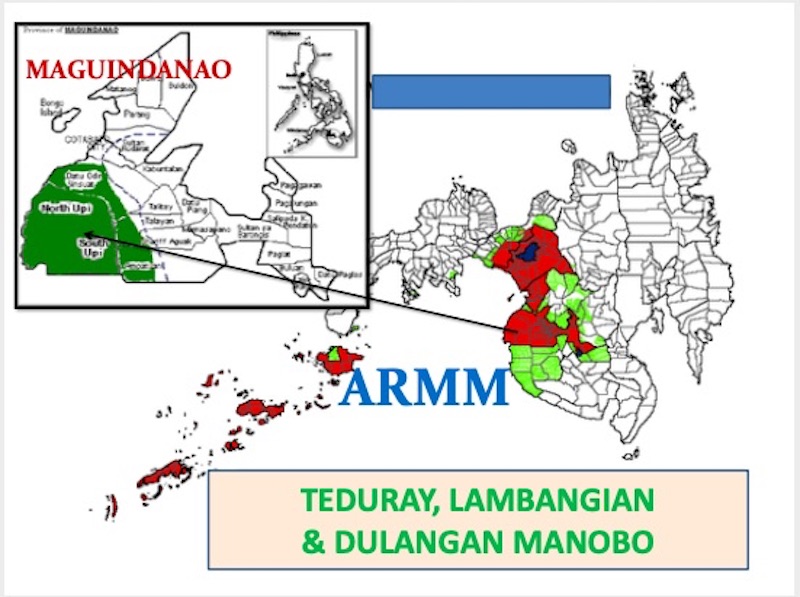

They did not want to take into account the fact that the new administrative boundaries crossed ancestral domains. Indeed, the consolidated claim to the ancestral domains of the Teduray and Lambangian tribes straddled the municipalities of Upi, Upi South and the southern parts of the municipalities of Datu Odin Sinsuat, Talayan, Guindulungan, Datu Unsay, Shariff Aguak and Ampatuan, all located in the province of Maguindanao. The NMIPs, and in particular the Lumad, were in the majority in the municipalities of Upi and Upi Sud. In fact, with the division of Maguindanao into two provinces, their voices will be even more inaudible.

Although they voted against this division, the Teduray and Lambangian votes were marginalized, as the plebiscite received resounding support. This was another aggravating factor when Typhoon Paeng struck, less than three months later. The worst-hit areas were Datu Odin Sinsuat, Datu Blah Sinsuat and Upi. The strained relations between the Maguindanao local governments and the BARMM government were highlighted, including in the search for humanitarian aid, with the former preferring to seek help from the national government13. These political quarrels therefore had an impact on the response to the disaster, particularly on those at Point Zero of the cyclone.

A question of solidarity

The political situation has more or less returned to normal in parts of the archipelago, notably in Manila, although militant trade unionists, human rights lawyers, inquisitive journalists and environmentalists remain at risk from henchmen and police harassment.

The situation is different in Mindanao. In the past, Muslim or popular movements and indigenous peoples’ organizations were able to collaborate, at least in a defensive capacity, as they were jointly victims of army operations and repression. The state of war was followed by a long period of negotiations with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), during which the MILF leadership (which dominated) explained that the question of Lumad rights should not be raised “so as not to complicate the peace process”, recalls Sonia. The MILF leadership implied that the demarcation of ancestral domains would take place once their power was well established. This is not the case.

In fact, as Sonia explains, the situation in Mindanao is deteriorating significantly. “Surveillance of associations defending human or social rights and freedoms is increasing, leaving activists under constant threat. The military’s sense of impunity is total. They resort to”red-tagging“, equating all those targeted with”communists“and creating a climate of witch-hunting”.

For the above-mentioned reasons, the situation is specifically precarious under BARMM and in the areas inhabited by the Indigenous Peoples. Lumad communities living on the coast are particularly vulnerable, but they are threatened everywhere, in the name of development (capitalist, extractivist, predatory). A development model that can only exacerbate the global climate and ecological crisis - but it has to be said that the Philippine oligarchies, whether Christian or Muslim, are not the only ones in the world to behave in this way.

“We really need international solidarity,” concludes Sonia. “We know that the situation is becoming increasingly difficult for the working classes in France too, in Europe, in North America... International attention is focused on Ukraine, a European war! We feel solidarity with you, a feeling of mutual solidarity.”

Pierre Rousset

GLOSSARY

AFP: Armed Forces of the Philippines

BARMM: Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

BTA: Bangsamoro Transition Authority

IPD: Internally displaced persons

IPRA: Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act

IPS: Indigenous Political Structures

Ips: Indigenous peoples

LGUs: Local Government Units

MILF: Moro Islamic Liberation Front

MIPA: Ministry of Indigenous Peoples Affairs

MNLF: Moro National Liberation Front

NCIP: National Commission for Indigenous Peoples

NMIPs: Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples

TJG: Timuay Justice and Governance

To send donations via ESSF

ESSF continues its financial solidarity campaign in Mindanao. Part of the donations are used to provide assistance to the Lumad people.

Donations can be given by cheques (in euros only, payable in France), direct bank transfers to our account or via Helloasso and PayPal.

Cheques

cheques to ESSF in euros only, payable in France, to be sent to:

ESSF

2, rue Richard-Lenoir

93100 Montreuil

France

Bank Account:

Crédit lyonnais

Agence de la Croix-de-Chavaux (00525)

10 boulevard Chanzy

93100 Montreuil

France

ESSF, account number 445757C

International bank account details :

IBAN : FR85 3000 2005 2500 0044 5757 C12

BIC / SWIFT : CRLYFRPP

Account holder : ESSF

Through PayPal

To access PayPal use the email address contact@europe…

Or click on the PayPal icon on the home page.

Through HelloAsso

You can also send money through the association HelloAsso: see its button on ESSF English home page: http://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?page=sommaire&lang=en

Or go directly to:

https://www.helloasso.com/associations/europe-solidaire-sans-frontieres/formulaires/1/widget

- 1This collective term has no “s”.

- 2Task Force Barat, ESSF (article 64680), Mindanao (Philippines) - Typhoon Paeng Tragedy in Tëduray and Lambangian Fusaka Ingëd: A Testimony of Neglect and Overdue Processing of Ancestral Domains Delineation.

https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article64680 - 3Task Force Barat Statement 2022

- 4The Worsening Human Rights Situation of the Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

- 5See notably Galileo de Guzman Castillo, Focus in the Global South, 12 April 2022, available on ESSF (article 63565), Philippines: Inward Flows And Undertows: Investments In The Bangsamoro:

https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article63565 - 6The barangay is the smallest local administrative unit in the Philippines.

- 7The TJP is the Lumad’s self-governing framework, which for a long time operated clandestinely, before becoming visible. It regulates collective life and dispenses justice according to the Lumad’s own rules.

- 8See ESSF (article 67583), Mindanao (Philippines): Desperate situation of non-Moro indigenous peoples:

https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article67583 - 9Originally from the province of Maguindanao.

- 10Task Force Barat, ESSF (article 64680), Mindanao (Philippines) - Typhoon Paeng Tragedy in Tëduray and Lambangian Fusaka Ingëd: A Testimony of Neglect and Overdue Processing of Ancestral Domains Delineation.

https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article64680 - 11https://www.rappler.com/nation/mindanao/results-maguindanao-plebiscite-2022/

- 12https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1658439/milf-political-party-urges-supporters-to-back-maguindanao-split

- 13https://www.mindanews.com/peace-process/2022/11/disasters-and-transitions-in-the-bangsamoro-learning-and-teaching-moments-1/; https://www.mindanews.com/peace-process/2022/11/disasters-and-transitions-in-the-bangsamoro-learning-and-teaching-moments-2/