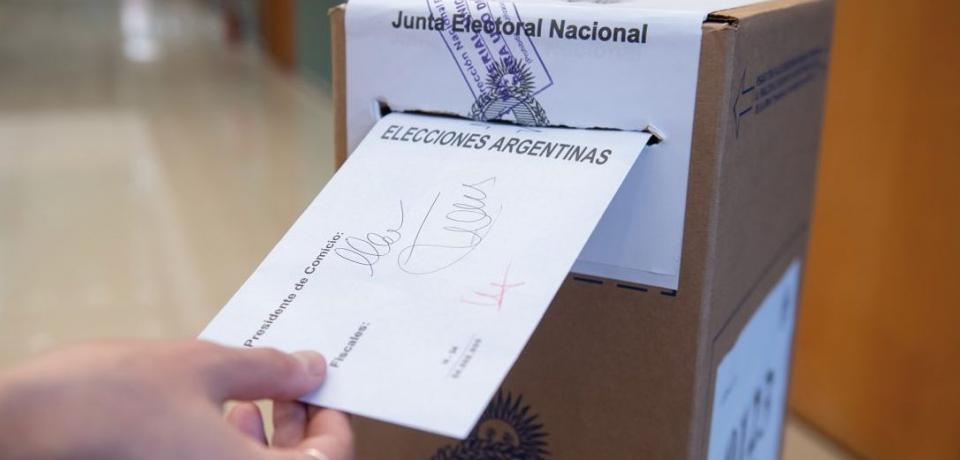

On Sunday, 12 September 2021, simultaneous and mandatory open primaries (PASO) took place in Argentina.1 The results surprised the ruling party, the opposition and the main analysts.

If the voting pattern was repeated in the parliamentary elections to be held in two months’ time, the ruling Frente de Todos (FdT) coalition would lose its quorum of senators while the right-wing Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) would become the biggest majority of deputies and would be consolidated as an alternative by 2023. These elections also showed the advance of an ultra-neoliberal and anti-political right (with many points of contact with {Bolsonarismo} in Brazil and Vox in Spain) and as a counterpart the presence of an anti-capitalist left that managed to position itself as a third force at the national level, of course a long way behind the hegemonic forces.

Moods

The pre-election climate was not the best. This was not just because of the pandemic, fears of contagion, even the resurgence of the Delta variant. Apathy and a lack of interest dominated the stage as a reflection of a campaign devoid of ideas and serious political debate, as verified in the abstention rate of 33%, the worst record since the restoration of the liberal democratic regime.

This is borne out by analyses at both the quantitative (surveys) with resistance to being interviewed (going from 10 to 25%) and qualitative (focus groups) levels: disillusionment and anger at the lack of solutions to the main problems affecting working people (pandemic, structural fall in wages and pensions, unemployment, very high inflation and increased poverty within the framework of a strong adjustment of fiscal spending).

Finally, something more fundamental: a kind of disconnection of citizens with politics and politicians on the one hand and on the other the negative attitude to the lack of a serious debate on the specific problems of the country. The lack of involvement of young people (seven million voters are between 16 and 25 years old), contrary to what happened a decade ago, completes the picture.

All this resulted in a campaign as anodyne as it was empty. The past (who indebted the country the most or whether it was right to sustain the original extensive lockdown) was discussed more than the future (proposals to get out of the crisis or a post-pandemic country project). For the ruling FdT, it was about winning 10 new deputies, to achieve a quorum and its own majority. For the right-wing opposition coalition, JxC, the goal was simply negative, to impede the government’s objectives with the banal argument that “we are 7 seats from being Venezuela”

The results

Juntos por el Cambio [Together for Change], which triumphed in 17 of the 24 eligible districts, won 40% of the vote while the Frente de Todos [Front of All] won 30.55% (the lowest percentage obtained by Peronism since 1983), a difference of just over two million votes. The FdT did not increase its number of deputies, as was its objective, but lost nine, while JxC retained the ones it already had but did not add any new ones. The ultra-neoliberal right was present in only two districts obtaining together 7.13% and four deputies. It is possible that a portion of those votes came from deserters from JxC, but it is also possible that many of those votes were cast by young people (even first-time voters) unhappy with the overall situation and seeing no prospects for the future. (In Argentina you can vote from the age of 16 although your vote is not mandatory, as if it is for those over 18)

The anti-capitalist left

With 7.29% of the votes (1,600,000) the anti-capitalist left had an electoral success that at the national level can be considered historic, especially in the existing polarizing framework. Of the group of parties that make up this space – all of Trotskyist extraction, inexplicably divided electorally – the Frente de Izquierda y los Trabajadores-Unidad (FIT-U) – which brings together the Partido Obrero (PO – Workers’ Party), Partido de los Trabajadores por el Socialismo (PTS – Workers’ Party for Socialism), Izquierda Socialista (IS – Socialist Left) and Movimiento Socialista de los Trabajadores (MST – Socialist Workers’ Movement) - was the only force capable of having parliamentary representation. It garnered 6.25% of the vote, retaining its current two seats, and could win two more. It is noteworthy that it enjoyed especial success in two of the main districts of the country (the Federal Capital and the strategic Prov. of Buenos Aires) but also in other provinces with percentages ranging from 7 to 9%, up to a striking 23% in the northern province of Jujuy (the candidate, and possible deputy, is of indigenous origin). The votes obtained by the left come from the sectors hit by the crisis, with a strong working class and popular content, although support also came from the feminist, environmentalist and anti-extractivist movements.

An additional fact is that the MST presented its own candidacies in the internal, obtaining good percentages in several districts, which raises the question of how to expand the front, integrating other groupings more identified with the so-called popular left and which are part of the richness and diversity of the Argentine anti-capitalist left.

Between now and November and beyond

Despite being a primary election for the future parliamentary elections, the presidential elections of 2023 overshadowed the entire campaign. From this perspective the provisional results pending in November are already imposing the internal reorganization/reconfiguration of the two large coalitions that hegemonized the vote. In the ruling party there is also a possible ministerial restructuring of the government to face both the economic crisis and its own political crisis.

In the case of the right-wing opposition, which had internals in numerous districts, the results strengthened the less confrontational wing in two ways: which state policies to agree to get out of the crisis and the selection of the next presidential candidate, for which several candidates have already announced themselves. In the ruling party, the electoral punishment opened a great debate at two levels: first, how to recover votes for the November parliamentary elections – or at least reduce the level of defeat – taking into account that in the final elections more citizens always vote than in the primaries. A more distributive policy is on the horizon immediately, but this requires more monetary issuance and reconciling that with the need for agreements with the IMF and the Paris Club, and their conditions regarding the fiscal deficit, so as not to go into default again. Then, how to go through the two remaining years of government recovering presidential possibilities, when today its main figures have been very devalued. The terms of the debate move between a so-called “radicalization”, understood as greater controls and greater state intervention, and agreement with the opposition and the most concentrated capital, offering as a counterpart that Peronism has once again demonstrated in these two years of government its recognized ability to sustain governability avoiding social explosion.

The vote for the anti-capitalist left is useful to strengthen critical discourses towards the system, to advance demands, to denounce the agreement with the IMF, to question the critical sectors within the government but also to reinforce a presence in mobilizations. The next two years will be decisive, either the government changes course in a more progressive and popular sense or it will end up paving the way to the right's return.

- 1These primary elections were established in 2009 for each general election. All parties must take part, including both parties with internal factions and parties with a single candidate list. Citizens may vote for any candidate of any party, but may only cast a single vote. Parties must also get 1.5% or higher of the vote to be allowed to run in the main election.These primary elections were established in 2009 for each general election. All parties must take part, including both parties with internal factions and parties with a single candidate list. Citizens may vote for any candidate of any party, but may only cast a single vote. Parties must also get 1.5% or higher of the vote to be allowed to run in the main election.