Spain is often regarded as a model in the fight against gender-based and sexual violence. Maria from Anticapitalistas spoke to l’Anticapitaliste.

What has been the impact of the law on “comprehensive protection measures against domestic violence” passed in 2004?

The law was a fundamental step in recognising the existence of structural violence that women suffer as women, as a manifestation of the historically unequal power relations between women and men. Male violence is expressed in many areas, although its application has been reduced to cases where the violence is perpetrated by a partner or ex-partner. This limitation was criticised by the feminist movement and, almost 20 years later, the need for a law to combat sexual violence has become clear, giving reason to this criticism. The impact could perhaps have been greater if, from the outset, a comprehensive response to the violence suffered by women in all spheres had been provided, and not just focused on the private sphere of conjugal or couple relationships.

As a comprehensive law, it recognises that the approach and responses to this violence must be multidisciplinary and includes measures in many areas: prevention, education, media and advertising, support for victims, etc. However, it focuses more on the criminal dimension, as the law itself states: “the criminal response that all manifestations of violence regulated by law must receive will be tackled resolutely”.

In the area of advertising, it can be seen that the law has not been applied in a “resolute” manner. Over the past 20 years, we have seen numerous campaigns by the women’s movement denouncing, for example, the pink and blue toy catalogues every Christmas, but few if any measures, or even fines, have been applied against the companies responsible to ensure that this does not happen again. In terms of education, much greater progress could have been made, and in a much stronger way, but this has not been the case. With the rise of the far right and its presence in the institutions, the few advances that have been made in the field of education have been called into question, with initiatives such as the “parental pin” proposed by the far right party VOX a few years ago (providing for parental authorisation for children’s participation in activities related to issues of gender violence, among others).

Applying the penal code as the main measure is the failure of violence prevention, it’s the last response of the state, it shouldn’t be the first or the main one. The idea is that if we continue to generate “healthy children of patriarchy”, we cannot think that by severely applying the punishment they deserve for the violence they perpetrate, the problem will be solved. It’s not because we increase penalties that violence will decrease, there’s enough evidence to support that. It is by focusing on structural and symbolic violence, rather than trying to determine the sanctions to be applied in the case of direct violence, that we will succeed in reducing violence and building societies free from oppression.

Repressive measures have succeeded in changing common sense with regard to the recognition of violence that used to be legal, such as punishing your wife with a slap if she doesn’t make dinner, or hitting her for cheating on you, because these actions now carry a criminal penalty. “You can no longer act as you did before”. They have also made it possible to avoid reducing violence to its physical form, and it is now hard to find anyone who doesn’t know that violence can also be and is verbal and psychological, and that it generates after-effects in the same way as physical violence.

But the application of a well-oiled repressive machinery, without other accompanying responses, has also had perverse effects, such as the climate of victimisation in which men now live. In today’s imagination, there is the idea that a woman has the power to ruin a man’s life simply by lodging a complaint, whereas her protection before the courts and this power are not so automatic. The insistence on false complaints (everyone claims to know of cases where women have used the law to take revenge), the fact that men claim to be criminalised and the continual “Not all men” show how far we have failed to reverse the narrative that violence is an individual problem and not a social one.

For many, this change in common sense has been experienced as something imposed, rather than as a logical step forward in rights and social justice.

Has the number of feminicides been significantly reduced?

According to data from the National Statistics Institute (www.ine.es) on the number of women murdered by their partner or ex-partner between 1999 and 2023, there has been no significant reduction in feminicide. In 1999, there were 54 feminicides and last year 58. The years with the lowest number of victims (49) were 2016, 2017, 2021 and 2022, and the year with the highest number (76) was 2008.

While it is true that in the last decade the number of feminicides has fallen compared to the previous decade, not reaching 60 victims, whereas in the previous decade it was more common to exceed this number, I believe that we are still a long way from being able to say that this reduction is significant. Nevertheless, the trend is towards a reduction.

In France, we are debating the introduction of the notion of consent in the legal definition of rape. A bit like the “Sólo sí est sí” [Only a yes is a yes] law of 25 August 2022 does? What did it allow?

I really think it’s too early to know what the law has achieved, in addition to the latest reform that the PSOE has incorporated, from what I understand, it gives rise to a legislative framework very similar to the one we had in reality. The media noise generated around this issue has not exactly been positive, and it will have many undesirable effects (for example, the announcement of the release of rapists by reducing the penalties of the law has reinforced punitive populism), and the “Errejon case”, which occurred only a few weeks ago, puts the finishing touches to the issue in a negative way.

The “Soló si es sí” campaign is in response to criticism from a feminist movement that has highlighted a highly sexist and patriarchal judicial system. One of the movement’s main demands was to eliminate the distinction between abuse and aggression, to broaden the concept of sexual aggression, emphasising our sexual freedom to decide on the relationships we have, the practices we indulge in, the limits we set ourselves, to be a subject and not just an object of desire and pleasure.

But this law was not conceived by feminist groups as a whole, and it is a mistake that its development was limited to a dialogue between institutional feminism and an obsolete and patriarchal judiciary, without the autonomous feminist and civil movement being able to play a specific role. Thus, while the law echoes the demands of the movement, it also incorporates its punitive tendency, focusing on judicialisation and giving a particular voice to the most abolitionist approaches. Abolitionism, criminalisation and judicialisation tend to go hand in hand; indeed, in its original formulation, it included issues such as penalising landlords for renting properties used for prostitution, reflecting the abolitionist and criminalising attitude towards sex workers. Also absent from the debate was a commitment to a new formulation of feminist justice.

It is a law designed “against sexual assault”, not a law “for sexual freedoms”, despite its name, but it is nevertheless a major step forward: it emphasises the rights of victims, rather than focusing on perpetrators, and does not require a criminal complaint to be made in order to access remedies, which is what happened in the law on gender-based violence. Focusing on this rather than on whether or not violence is perpetrated is a step forward, even if it generates debate about consent and what has been called the shift from a “culture of violence” to a “culture of consent”.

Does putting the clear and manifest expression of affirmative consent put the victims at the centre?

The transition from a demonstration of violence to a demonstration of consent is not necessarily simpler or more liberating for the victim; we still need to change the ideas that justify aggression and exonerate aggressors from all responsibility. How do we deal with the fact that many women are sexually assaulted in the context of family and friends? Dismantling what we call the ‘rape culture’ remains a task to be accomplished. Consent as such is a problematic and ambiguous concept: what behaviours and practices are recognised as manifestations of consent, what are they, and according to what cultural codes should we understand non-verbal consent? The logic of affirmative demonstration implies an understanding that all sexual intercourse is potentially a sexual assault from which we must protect ourselves. It implies a vision of sexuality full of fears and dangers, in which women are potential victims and not subjects with the right to enjoy their bodies and their sexuality. All this while the debate revolves around punishment and involves regulating and criminalising.

Assuming that without consent, “without yes, there is sexual assault” places many sexual relationships governed by other logics in potentially punishable areas.

The commitment to a culture of consent makes it desirable to regulate and standardise the sexual process, which affects the very process of development, discovery, experimentation and the ability to set one’s own limits. I’m not against consent, but I am against punitive regulation of consent. Unilateral consent on the part of women makes us reluctant subjects. We take it for granted that we are the ones who must consent, that we are not attracted to sex, that we do not desire, that we do not touch, that we do not take pleasure? It’s the idea that “they always want it”, or that we don’t like it. It’s more a question of wanting to have sex or not, than of consenting. That’s why I think it’s better to talk about sexual freedom rather than consent.

Beyond the legal aspects, how is society progressing in terms of gender violence?

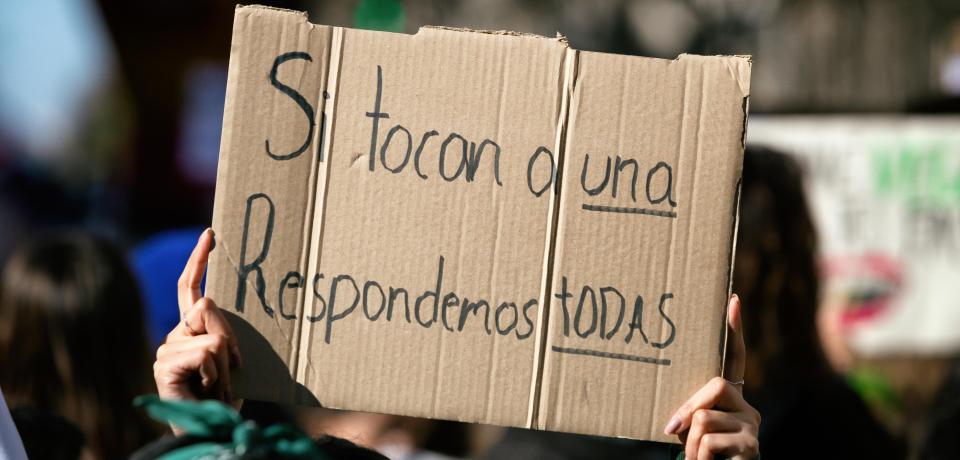

After a few years in the heat of strike action, when it seemed that feminism was hegemonic and that progress had been made, we are now witnessing with horror the macho counter-reaction. It seems that the gap between the sexes is obvious and that men have been left behind. In the words of bell hooks, “there has never been a collective and determined demand for boys and men to join the feminist movement to liberate themselves from patriarchy”, and I think this is one of the tasks ahead of us.

We have come a long way and we know that legislative changes are important, even if they have their limits. We won’t solve the problem of violence simply by changing the laws. We need real and profound changes in social structures. If male violence, as we know, is structural, until we break down patriarchy and live in non-patriarchal societies, the direct violence we suffer will not stop.

Translated by International Viewpoint from l’Anticapitaliste.