“Of course I am an ecosocialist, as are the indigenous peoples — even if they do not use that term.”

Hugo Blanco is one of the figures in the struggle for emancipation in Peru. In the 1960s, he played an important role in the revolutionary mobilization of indigenous peasants against the four-century-old dominant agrarian regime — latifundism. During a self-defence action, a policeman was killed; Blanco was sentenced to death. Defended by Amnesty International, Sartre and de Beauvoir, he lived in exile in the 1970s: in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and then, in the aftermath of the coup against Allende, in Sweden. Returning home, he joined the Peasant Confederation and became a member of parliament, then a senator under the colours of Izquierda Unida — a coalition of left-wing organizations.

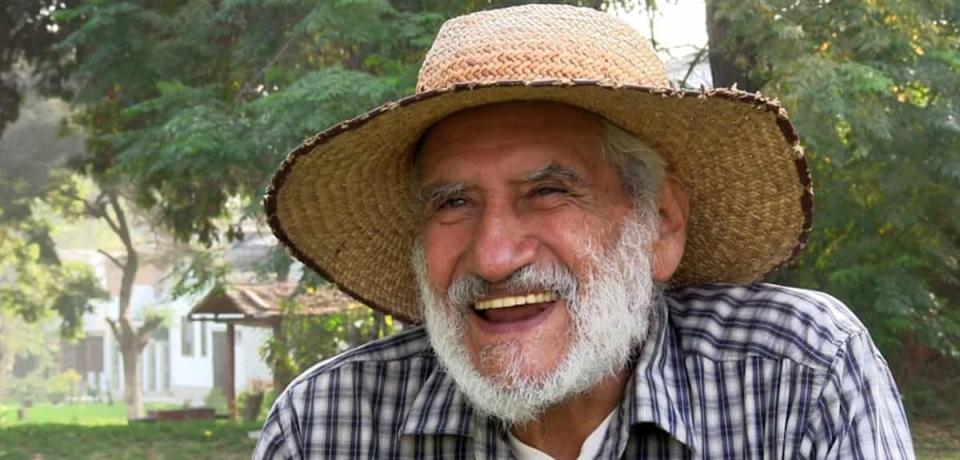

At the age of 86, he currently [2021] resides in Sweden, retired from ”political life”. Last month, during the screening of a documentary tracing his career, the Peruvian far right campaigned against him. This is an interview published in his native country in 2015: he looks back on his life as an activist.

Tell us about your life: were you a peasant or a student?

My mother was a small landowner and my father was a lawyer. He had a brother who was studying at La Plata (in Argentina). As I loved the countryside, I also studied agronomy there. My father paid for it. But as Eduardo Galeano says, I was born twice: the first was when I came into the world; the second was, as a child, when I learned that a landowner had marked the buttocks of a native with a hot iron. It had a big impact on me, it marked my life. When I was 13, we were three brothers — one was 19, the other 17. I was the only one who was free: they had been arrested as Apristas (members of the Peruvian anti-imperialist party, APRA). APRA and the Communist Party were persecuted. That also shocked me. I was inclined to turn to the indigenous people because the 1910 revolution in Mexico influenced Cuzco (a city in south-eastern Peru). Then I went to Argentina. There was a working-class reality there. Among the high school students, there was a study group in which we read Haya de la Torre, Mariategui and Gonzalez Prada — in such disorder. We wanted a university student to guide us but, of course, they were suspicious of talking to us: as APRA and the CP were particularly persecuted, we could have delivered them to the police unintentionally... Then I went through Bolivia and there was a lot of revolutionary literature. I did not know it then, but in 1952 there was a revolution there, during which a military government was overthrown.

What happened to your career as an agronomist? Did you abandon it?

Not at once. I wanted to join a left-wing organization. [...] So I started looking for an organization and that’s how I met the Peruvian Trotskyists: I was introduced to activists from the Argentine Trotskyist party. I joined them. The pro-imperialist coup against Peron was in the midst of being prepared — by the North Americans (he was overthrown in September 1955). The middle class supported this coup. I didn’t feel like I belonged in the university anymore. That’s why I decided to leave and go to work in the Berisso meat packing plant near La Plata.

How long did you stay there?

About three years. Then I went home. At that time, the idea was that the proletariat was the vanguard, and as there were no proletarians in Cuzco, I went to Lima to be in the factories. I went to work in a textile factory, but I had become accustomed to working in large factories, with 5 to 10,000 workers. Here, one was the boss’s godson, the other the foreman’s nephew — and there was no union! It was impossible to form one. So I left the textile factory to go to a metallurgical factory, but it was just as small. So I went to Chanchamayo, in central Peru ,to learn welding and then I went back to Lima, where I finally found a factory with a union. A Friol oil factory. I worked there, but Nixon, who was then vice-president of the United States, came to Peru: with several small left-wing groups, which did not include the CP or APRA, we prepared a counter-demonstration. It was much bigger than we had imagined. The repression came down on us; I had to leave the factory and go to Cuzco.

But how were you elected leader during the peasant uprisings in La Convencion (one of Peru’s 13 provinces) in the 1960s without ever having been a peasant?

I had learned that the proletariat was the vanguard, that it had to be brought to power and that it would solve everyone’s problems. I felt like an Indian at the time, and since the proletariat was the vanguard, I was also a proletarian. But when Nixon arrived, I had to flee to Cuzco and I found myself organizing the canillitas, the news vendors. I was their delegate to the Cuzco Federation of Workers. I understood that it was not a federation of workers, but, fundamentally, of artisans. And I understood that the vanguard was the peasants of La Convencion. When the editor of the Cuzco newspaper had me arrested — because of the canillitas — I found myself at the police station with a peasant leader, whom I had already met at the Federation, and he said to me,”They are going to release you tomorrow because there is no order from the judge, but they are going to send me to prison. I am concerned because three of the union leaders are already there. He was a leader of the Chaupimayo union. So I said, “Well, I’m going to Chaupimayo.” And he said, “Go and talk to the other leaders in prison.” I went there, I talked, they agreed that I had to go. That’s how I went to La Convencion and my life as a peasant started.

Did they accept you?

They accepted me because there were already three leaders in prison.

But how did they accept you? You are not especially “coppery”(an allusion to skin colour)...

Well, there are a lot of barefoot peasants who speak Quechua and are blond. With my daughter, who was from Sweden, we went to my district and she said,”Dad, these peasant women are whiter than me.” That’s right, there are corners where people are blond. To be indigenous is to work the land, to speak Quechua. I don’t know the origin of it but, if my features are not totally native, I have some characteristics.

And you speak Quechua.

Of course, of course. And a little Spanish too! (he jokes) Quechua seems to me to be a more complete language than Spanish.

This language became known during the uprisings in La Convencion and Lares in the 1960s. At the time, the problem of the Indian, as Mariategui said, was the problem of the land. If, from now on, the problem is the mining companies, does the problem of the land still arise?

One journalist said that I used to fight for the “land,” with small letters, and that I am now fighting for the “Earth” in capital letters. In Quechua, we do not have this problem because they are two different words. The arable land is “jallpa” and the planet Earth is “Pachamama”.

You were then a kind of Gregorio Santos(a Peruvian political figure), right?

For starters, I don’t believe in leaders. I don’t consider myself a leader, and I never have been. Second, I have always respected the indigenous characteristic that it is the community that is responsible, not the individual. Even when we took up arms, it was the masses who decided to defend themselves.

Even though you don’t think you’re a leader, the people have presented you as such…

Well, they see me that way because the system has domesticated us — some people are supposed to have been born to command and others born to obey.

[...] In any event, land reform occurred in those years. Is it because of the Chaupimayo uprising that you did it?

It is thanks to the organization of the peasantry of La Convencion.

Was an uprising necessary? Belaunde(then president of Peru) had promised reform, and he was taking care of it.

He made only a caricature of land reform, and he shot the peasants. Hence the coup d’état in 1968.

But wasn’t it the landowner Luna Oblitas who then killed seven peasants...

Yes. But the policy of Belaunde was to slaughter the peasants who had taken the land of Cuzco. What happened? The peasants organized themselves; they fought for the land; the government served the rich (like all governments to this day); they started the repression. So the people decided to defend themselves. Then they took us prisoner. But they saw that people reacted to that, to the point that they did not continue to repress. They even issued an agrarian reform decree, which they did not intend to comply with. It concerned only La Convencion and Lares. Two landowners agreed to do land reform on their haciendas — in Potreros and Aranjuez. As the law dictates, the best part was left to the landowners. Then the government officials went to the peasants in other places and they said, “We have come to give you the land by order of the government.” The peasants replied: “Here we do not need the land reform law of the government, here the land reform of the peasants has been done and it says that not an inch of land is left to the owner and not a penny is given to him. It was only in the two haciendas in question that the land reform of the government was carried out — in the others, it was the reform of the peasantry. We were in prison. Belaunde killed many people, and the military, worried because all this could provoke a revolution, decided to take power themselves to carry out the land reform. They were also supported by the industrial bourgeoisie, which was advancing and being motivated by the existence of the semi-feudal latifundia and by the fact that the peasants, with their land, would become buyers in the market. In other words, the bourgeoisie wanted land reform — that is why it supported Velascoo (putschist president, from 1968 to 1975).

To end up alongside Belaunde, in his second government...

(He interrupts) ... he continued to kill peasants.

History has it that he sent the minister”El Gaucho” Cisneros to fight the “abigeos” (cattle thieves”), who were terrorists, and that he massacred the peasants. But why does Belaunde have this image of a “democrat” then?

Because the bourgeoisie made him a democrat. The media, the judiciary, parliamentary majorities, prosecutors, everything is in the hands of the bourgeoisie. So it preaches to us that he is the”great democrat” — in quotation marks.

History is written by the winners.

Exactly. Obama is also a servant of transnational firms. Ollanta (president of Peru from 2011 to 2016), even worse.

After Velasco’s fall, Operation Condor began. Were you also a victim of this policy of eliminating opponents?

I was in jail when Velasco came in. A Communist Party leader came to me and said, “You’ve been in prison for less than seven years, you’re a long way from your 25 years. If you want, you can leave the prison tomorrow. If you commit to working on the land reform that Velasco is going to do, you’ll come out. I knew it would be a positive land reform, compared to Belaunde’s.

But it is one thing to be a member of Parliament, senator, parliamentarian, councillor, that the people have elected you and that you can do what you think; it is quite another to be a civil servant, such as former leftist Yehude Simon (President of the Peruvian Council of Ministers in 2008-2009,who said that the Bagua massacre was acceptable. (n June 2009, a clash between police and indigenous peoples threatened with eviction resulted in 33 deaths]. I did not intend to become a civil servant. In addition, we could have differences, which happened. I wasn’t going to talk politics with this lady, so I said, “No thanks, I’ve got used to prison.” But it happened that two other political prisoners agreed to work with Velasco: Béjar and Tauro. Then they had to give us all freedom. Once I was outside, they kept coming at me with the idea that I had to work for the government, otherwise I would “stay on the margins of history”. “I’m not interested in history”, I told them. I ended up saying, “You won, I will work with you, but on one condition. Let the land reform that I want not be carried out, nor the one that the government wants: let us ask each sector how it wants this reform. If they decide to break it up, it is done in that way; if they say “community,” it is done in that way; if they say “cooperative,” it is done in that way; etc.” That was a very good remedy: we are not going to ask a military government to be democratic. So they forbade me to leave Lima and then deported me to Mexico. So when I am asked what was the best government in Peru, I say that the least bad is the one that expelled me, the Velasco government.

We were talking about Operation Condor: were you in its sights?

I was deported by Velasco. When Morales carried out his putsch in 1975, it was a right-wing putsch. But, out of demagogy, he said that the deportees could return. I came back, they followed me, and then Morales deported me — to Sweden this time. Later, when the strike of 19 July 1977 shook the country2, the Morales government backed down and called for elections for a Constituent Assembly. My comrades presented me as a candidate. I came back and, again for demagogic reasons, they said that there would be a free space on television for the different parties to make political propaganda. I got this space right after a package of reforms and after the CGTP trade-union confederation had called a two-day strike. So I said, “Well, comrades, we just suffered a terrible blow. Regardless of whether people vote for me or for someone else, nothing will be solved by the elections but by the direct action of the people. The CGTP has called for a strike on July 27 and 28, so it is our duty to be united in this strike. Remember, that is our obligation. That’s all I did. But because this airtime was not intended for strike propaganda, but for election propaganda, I found myself in prison five hours later. They took the opportunity to pick up other leftists like Ledesma and Javier Diez Canseco. They put us on a plane and sent us to Jujuy (in Argentina), as part of Operation Condor, to disappear. When we got off the plane, a general said,”You are prisoners of war.” Fortunately, a journalist had taken a picture of the plane: they published it, so they couldn’t make us disappear.

What did you learn from those years in prison? What did you during them?

The”democrat” Belaunde, violating the laws under which every accused is presumed innocent, kept me in absolute secrecy for three years. I was supposed to be in Cuzco prison, but they sent me to Arequipa. Everything I wrote, including to my family, went through the censorship. When my family visited me, there was always a sergeant listening and only very close relatives could come in. When my mother came, as Spanish is an emotionally poor language, I spoke to her in Quechua: the sergeant forbade me to do that.

You must have learnt something in prison...

Of course. When I was in El Fronton, I was more relaxed. They could not keep me under surveillance because if they checked my mail, I would send it through another inmate. In order for things to calm down, I had to go on hunger strike — they wanted to isolate me. I learned a lot in prison. I was reading the publications of comrades from other countries, that sort of thing.

Moreover, in the struggles more or less of the guerrillas...

(He interrupts) ... This “guerrilla” thing, yes and no. If the guerrilla is a mobile armed group, okay, I was a guerrilla. But I don’t agree with the “focos theory (advocated in particular by Che Guevara) — that to make the revolution, it is important to gather some brave people who will start the armed struggle, and then the people will follow them. Here, too, I am a democrat: I believe that the people must decide. It was the assembly of the Provincial Peasant Federation that decided to defend itself in an armed manner, and it was the general assembly that asked me, by a unanimous vote, to organize self-defence.

[...] Have you ever killed anyone?

Yes. On the orders of the government, the police had decided in 1962 to abolish the land reform that was taking place in La Convencion. I was hiding in Chaupimayo and I heard on the radio that they themselves had said that they would start repressing Cuzco, killing peasants, then La Convencion, then Chaupimayo. In the province of La Convencion, they banned assemblies; they entered the union assemblies near the roads and dissolved the meetings at gunpoint. In one of these attacks, a landowner came to capture the union’s general secretary, along with a police officer. He could not find him. A 13-year-old boy was asked where his father was. The kid said he didn’t know and the landowner asked the police officer who was with him to give him his gun, and then threatened the boy at point-blank range:”If you don’t say where your father is, I’ll kill you!“ The little boy didn’t know, he started crying. The landowner fired. But he deflected the gun and broke the boy’s arm. This peasant came to me to complain: he asked me what authority he could turn to, but everyone was on their side! I told him to tell his comrades and the assembly decided to send people to hold the landowner to account. They decided to send an armed group, and it was up to me to lead it. We had to go past two police stations before we arrived.

We managed to dodge the first, but not the second. I told the comrades that a first group would pass, with a handgun, and that if it passed, the second group would follow. I was walking forward when I saw a policeman outside the front door: he was reading the newspaper, his nose screwed on it. But he’d seen us before. I told him I was going to talk to him, I told him what had happened at the Hacienda in Cayara. I said,”They are sending us to ask this landowner to account for his actions. But because he is armed and we do not have enough weapons, we have come here to get some.“ When I said that, I pulled out my gun and pointed it at him.”Put your hands up, we are taking the weapons, no one will be hurt. Then we will leave.” That is what I said. What I didn’t know was that he was the policeman who had accompanied the owner! I found out later. So this man drew his gun from his pocket and I shot him. He managed to shoot before, but the bullet hit the roof. One more second and I was dead.

What about the other police officers at the station?

I took his gun and shots started coming from another room. We all went out and my companions surrounded the station. I said,”You have a thatched roof and we have matches: go!” But they didn’t want to give up. I had put a stick of dynamite in a corner, but they still didn’t want to give up. I threw a homemade grenade made with a can of Gloria milk: people started coming, and the guard came out. I said,”Don’t touch him, a prisoner is sacred.” They brought him in and he told me there were only two of them. He told me to let him take care of his partner. I saw that my comrades were already going out with the guns. The second guard was injured: I asked people to call the village doctor, but they didn’t want to. I told them to go with the unarmed guard and if they needed medication, they should ask me — but what they asked for was a candle. I had shaved so that I would not be recognized, but as a man had been shot, when I left I said to the policeman:”My name is Hugo Blanco, I was the one who shot him.” I didn’t want them to go on a witch hunt. Then we went to the hacienda...

[...] Do you think you can be president of Peru?

(Laughs) Impossible. We Trotskyists participated in the elections to take advantage of the election campaign to spread our ideas. I am not going to dream of being president. It’s stupid to suggest that a revolutionary is going to be president.

Yet this is what happened with Mujica in Uruguay.

What kind of revolutionary is he, who passes a mining law without consultation? There are progressive governments that we support, that face the Empire, that fight against external aggression, like Evo Morales, Chavez,

Correa, etc., but when they clash with the people, we obviously support the people.

[...] Tell me, at your age, having been several times close to death, do you think about it? Are you afraid?

I have never been afraid of death. When I was in Arequipa prison, where I was held incommunicado for three years, they said ,“it’s okay we’ve softened this one”. They said there was going to be a hearing (which should have taken place in Cuzco, but they took me to Tacna).”It’s 25 years in prison or the death penalty,” they told me.”Yes, my lawyer told me,” I replied. They told me that there was a way to save myself: play sick and be deported to a country of my choice. I said,”Thank you, I’m perfectly healthy.” I wasn’t going to miss this audience! We were going to unmask what the latifundia were, what was the role of the police... I didn’t let myself be corrupted. At the hearing, they made propaganda on the radio saying that the”criminals” were going to be tried. It took place in the barracks of the Guardia Civil. My comrades had already been told, “It’s easy for you to get out of prison. It’d enough for you to say: ’We are semi-literate peasants and the communist Hugo Blanco deceived us’”. When I entered the courtroom and saw my comrades, after three years in detention, I shouted, “Land or death!” And they replied, “We will win!” Their idea of putting everything on my back was completely screwed up. The court was composed of officers of the Guardia Civil. But it was with them that we had had the confrontation, so they were judge and party. I stood up and said, “In this room, the only criminals are those who sit as a court. Not only are they criminals, but they are also cowards because they did not dare to fight: they sent the cholitos (a derogatory term for the mestizo natives sent to the front line by the colonial government). “

[...] I told them that if the social changes in La Convencion deserved the death penalty, then they should kill me. But that “whoever kills me should do so with his own hand, so that he does not stain with my blood the hands of the civil and republican guards because they are sons of the people, therefore my brothers.” I said that in pointing out the person who called for the death penalty. One last time, I shouted “Land or death!” and not only my comrades, but the whole room replied, “We will win!” So they didn’t dare sentence me to death.

[...] That said, how would you like death to come to you?

First of all, I don’t really want it to! That is why my fourth exile was voluntary: here I was sentenced to death by both the intelligence services and the Shining Path. I decided to leave the country and went to Mexico to be with my children. I want to live because we have to end the present system so that the human species can survive. But when death comes, it will come, and that is all.

Original publication in Castilian, January 2015 in ipdrs. Translated by International Viewpoint from the French abridged version published, January 2021 in Ballast.

To learn more about Hugo Blanco read Hugo Blanco – a revolutionary for life, by Derek Wall published by Resistance Books and Merlin Press, 2017.