In this text, Michael Löwy explains Lenin’s political trajectory, from the classical, statist position of the Second International on the seizure of power by the proletariat, to his Marxist philosophical conceptions.

“A man who talks that kind of stupidity is not dangerous.”(Stankevitch, a Socialist, April 1917).

“That is raving, the ravings of a lunatic!” (Bogdanov, a Menshevik, April 1917).

“They’re mad dreams...” (Plekhanov, a Menshevik, April 1917).

“For many years Bakunin’s place in the Russian revolution has remained unoccupied; now it is occupied by Lenin.” (Goldenberg, an ex-Bolshevik, April 1917).

“On that day [4 April] Comrade Lenin could not find any open sympathizers even in our own ranks.” (Zalezski, a Bolshevik, April 1917).

“As for the general scheme of Lenin, it seems to us unacceptable, in that it starts from the assumption that the bourgeois democratic revolution is ended, and counts upon an immediate transformation of this revolution into a socialist revolution» (Kamenev, in an editorial in Pravda, organ of the Bolshevik Party, 8 April 1917).

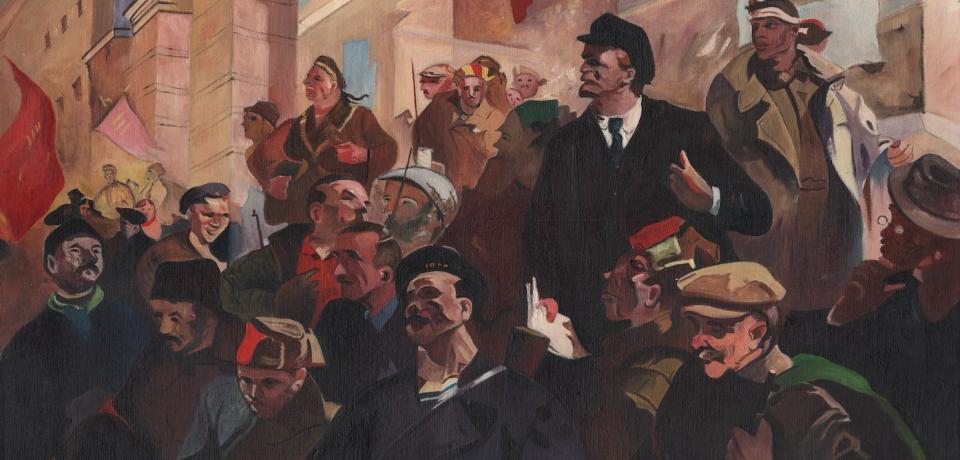

Such was the unanimous reception accorded by the official representatives of Russian Marxism to the heretical theses that Lenin had exposed, first before the crowd gathered in the Finland Station square in Petrograd, from the top of an armoured vehicle, and then on the day following before the Bolshevik and Menshevik delegates of the Soviet: the “April Theses”. In his famous memoirs, Sukhanov (a Menshevik turned Soviet official) testifies that Lenin’s central political formula – all power to the Soviets – “echoed like a thunderclap from a clear blue sky” and “stunned and confused even the most his faithful of his disciples.” According to Sukhanov, a Bolshevik leader even declared that “this speech [by Lenin] had not sharpened the differences within social democracy, but, on the contrary, suppressed them, because there could only be agreement between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks in face of Lenin’s position.”1

The Pravda editorial of 8 April confirmed for a moment this impression of anti-Leninist unanimity; according to Sukhanov “it seemed that the Marxist rank and file of the Bolshevik party stood firm and unshakable, that the mass of the party was in revolt against Lenin to defend the elementary principles of the scientific socialism of the past; alas! we were mistaken!” 2

How are we to explain the extraordinary storm which Lenin’s words raised and this chorus of general condemnation that came down on them? Sukhanov’s simple but revealing description suggests the answer: Lenin broke precisely with the “scientific socialism of the past”, with a certain way of understanding “the elementary principles” of Marxism, a way that was, to a certain extent, common to all currents of Marxist social democracy in Russia. The perplexity, confusion, indignation or contempt with which the April theses were received by both Menshevik and Bolshevik leaders are only the symptom of the radical break they imply with the tradition of “orthodox Marxism” of the Second International (we are referring to the hegemonic current and not to the radical left: Rosa Luxemburg, etc.) Tradition whose materialism - mechanical - deterministic - evolutionary crystallized in a rigorous and paralyzing political syllogism:

“Russia is a backward, barbaric and semi- feudal country.

“It is not ripe for socialism.

“The Russian revolution is a bourgeois revolution.

QED

Rarely has a theoretical turning point been richer in historical consequences than the one inaugurated by Lenin in his speech at the Finnish station in Petrograd. What were the methodological sources of this turning point? What is the specific difference of your method from the canons of the “old” Marxist orthodoxy?

Here is Lenin’s own response, in a polemical writing directed precisely against Sukhanov, in January 1923: “They all call themselves Marxists, but their conception of Marxism is impossibly pedantic. They have completely failed to understand what is decisive in Marxism, namely, its revolutionary dialectics.”3 His revolutionary dialectic: here, in brief is the geometric location of Lenin’s break with the Marxism of the Second International and, to a certain extent, with his own “old-time” philosophical consciousness. A rupture that began the day after the first Great War was fuelled by a return to the Hegelian sources of Marxist dialectics and led to the monumental, “mad” and “delirious” challenge of the night of 3 April 1917.

“Old Bolshevism” or “Old Marxism”: Lenin before 1914

One of the first sources of Lenin’s philosophical thought before 1914 was Marx’s The Holy Family (1844), which he read and summarized in a notebook in 1895. He was especially interested in the chapter titled: “Critical Battle against French Materialism”, which he calls “one of the most valuable in the book”.4 However, this chapter constitutes precisely the only writing by Marx where he uncritically “adheres” to the French materialism of the 18th century, which he presents as the “logical basis” of the communism. The quotes extracted from this chapter of The Holy Family are one of the shibboleths5 that allow us to identify “metaphysical” materialism in a Marxist movement.

On the other hand, it is an obvious and well- known fact that Lenin was highly dependent, philosophically, on Plekhanov at that time. Although politically much more flexible and radical than his teacher, who after the breakup of 1903 became the main theoretician of Menshevism, Lenin accepted certain fundamental ideological premises of Plekhanov’s “pre-dialectical” Marxism and its strategic corollary: the bourgeois character of the Russian revolution. Without this “common basis” it is difficult to understand that, despite his severe and uncompromising criticism of the “tailending” of the Mensheviks in relation to the liberal bourgeoisie, he was able to accept, from 1905 to 1910, several attempts at reunification of the two factions of Russian social democracy. Furthermore, it was at the time of his greatest political rapprochement with Plekhanov (against liquidationism 1908-1909) when he wrote Materialism and Empirio-criticism, a work in which the philosophical influence of the “father of Russian Marxism” is visible and legible.

What is notable and completely characteristic of Lenin before 1914 is that the Marxist authority he often claimed in his polemics against Plekhanov was none other than… Karl Kautsky. For example, he sees in an article by Kautsky on the Russian Revolution (1906) “a direct blow to Plekhanov” and enthusiastically emphasizes the coincidence between Kautsky’s and Bolshevik analyses: “A bourgeois revolution, brought about by the proletariat and the peasantry in spite of the instability of the bourgeoisie—this fundamental principle of Bolshevik tactics is wholly confirmed by Kautsky.”6

A close analysis of Lenin’s main political text of this period, Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution (1905), shows with extraordinary clarity the tension in Lenin’s thought between his general revolutionary realism and the limits imposed on it by tight straitjacket of the so- called “orthodox” Marxism. On the one hand, we find luminous and penetrating analyses of the inability of the Russian bourgeoisie to carry out a democratic revolution, which can only be achieved through a worker-peasant alliance that exercises its revolutionary dictatorship. He even talks about the leading role of the proletariat in this alliance and, at times, seems to touch on the idea of an uninterrupted transition towards socialism: “It [the democratic dictatorship] will not be able (without a series of intermediary stages of revolutionary development) to affect the foundations of capitalism..”7 With this short parenthesis, Lenin opens a window onto the unknown landscape of the socialist revolution, but only to immediately close it and return to the closed space, circumscribed by the limits of orthodoxy. These limits are found in the numerous formulas of Two Tactics, where Lenin categorically reaffirms the bourgeois character of the Russian revolution, and condemns as “reactionary” the idea of “seeking salvation for the working class in anything save the further development of capitalism.”8 Marxists are absolutely convinced of the bourgeois character of the Russian revolution. What does this mean? It means that the democratic reforms in the political system and the social and economic reforms, which have become a necessity for Russia, do not in themselves imply the undermining of capitalism, the undermining of bourgeois rule; on the contrary, they will, for the first time, really clear the ground for a wide and rapid, European, and not Asiatic, development of capitalism; they will, for the first time, make it possible for the bourgeoisie to rule as a class.

The main argument he presents to support this thesis is the “classical” theme of “pre-dialectical” Marxism: Russia is not ripe for a socialist revolution: “The degree of economic development of Russia (an objective condition) and the degree of class consciousness and organization of the broad masses of the proletariat (a subjective condition inseparably connected with the objective condition) make the immediate complete emancipation of the working class impossible. Only the most ignorant people can ignore the bourgeois nature of the democratic revolution which is now taking place”.9The objective determines the subjective, economy is the condition of conscience: here, in two words, Moses and the Ten Commandments of the materialist gospel of the Second International, which crushed with its weight the brilliant political intuition of Lenin.

The formula that was the quintessence of pre-war Bolshevism, of the “old Bolshevism,” reflects at its heart all the ambiguities of the first Leninism: “the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.” Lenin’s profoundly revolutionary innovation (which radically distinguished him from the Menshevik strategy) is expressed in the flexible and realistic formula of worker and peasant power, a formula of an “algebraic” nature (Trotsky said) where the specific weight of each class is not determined a priori. On the other hand, the apparently paradoxical term “democratic dictatorship” is the motto of orthodoxy, the visible presence of the limits imposed by the “Marxism of yesteryear”: the revolution is only “democratic”, that is, bourgeois; premise that, as Lenin wrote in a revealing passage, “is necessarily derived from the entire Marxist philosophy” that is as conceived by Kautsky, Plekhanov and the other ideologues of what was agreed to be called at the time “revolutionary social democracy”.10

Another theme of Two Tactics that attests to the methodological obstacle that the analytical character of this Marxism constituted is the explicit and formal rejection of the Paris Commune as a model for the Russian revolution. According to Lenin, the Commune made a mistake because it did not know how to “distinguish between the elements of a democratic revolution and those of a socialist revolution”, because it “confused the tasks of fighting for a republic with the tasks of fighting for Socialism”. Consequently, “it was a government such as ours [the future revolutionary provisional government, ML] should not be.” 11We will see later that this is precisely one of the nodal points through which Lenin will undertake, in April 1917, the wrenching revision of the “old Bolshevism.”

The “break” of 1914

“It is a forgery of the German General Staff!” Lenin shouted when they showed him the copy of Vorwärts (organ of the German SD) with the news of the socialist vote in favour of war credits on 4 August 1914.

This famous anecdote (as well as his obstinate refusal to believe that Plekhanov had spoken in favour of the “national defence” of tsarist Russia) illustrates both the illusions that Lenin had about “Marxist” social democracy, and his astonishment at the bankruptcy of the Second International and the abyss that growing between him and the “ex-orthodox”…” who had become social patriots.

The catastrophe of 4 August was for Lenin striking proof that something was rotten in the Danish kingdom of official Marxist “orthodoxy.” Therefore, the political bankruptcy of this orthodoxy led him to a profound revision of the philosophical premises of Kautsko- Plekhanovist Marxism. “The bankruptcy of the Second International, in the first days of the war, encouraged Lenin to reflect on the theoretical foundations of such a profound betrayal.”12 One day we should precisely reconstruct the journey that took Lenin from the trauma of August 1914 to Hegel’s Logic, just a month later. Simple desire to return to the sources of Marxist thought? Or the lucid intuition that the methodological Achilles heel of the Marxism of the Second International was the lack of understanding of dialectics?

Whatever the case, there is no doubt that his vision of Marxist dialectics was profoundly transformed. Proof of this is not only the text of the Conspectus of the Shorter Logic itself, but also the letter he sent on 4 January 1915, having barely finished reading (17 December 1914) Hegel’s Science of Logic, to the editorial secretary of Éditions Granat . to ask if “there was still time to make [to his Karl Marx] some corrections to the section on dialectics”.13 And it was not at all a “passing enthusiasm” since, seven years later, in one of his last writings On the Significance of Militant Materialism (1922) he called on the editors and contributors of the party’s theoretical magazine Pod Znamenem Marksizma to be ““Society of Materialist Friends of Hegelian Dialectics”. He insists on the need for a “systematic study of Hegelian dialectics from a materialist standpoint”, and even proposes to “print in the journal excerpts from Hegel’s principal works, interpret them materialistically and comment on them with the help of examples of the way Marx applied dialectics.”14

What were the tendencies (or at least the temptations) of the Marxism of the Second International that gave it its pre-dialectical character?

1. First of all, the tendency to erase the distinction between the dialectical materialism of Marx and the “old”, “vulgar”, “metaphysical” materialism of Helvetius, Feuerbach, etc. Plekhanov, for example, manages to write something surprising: that Marx’s theses on Feuerbach “n no way eliminate the fundamental propositions in Feuerbach’s philosophy, but only correct them... The materialist views of Marx and Engels, however, developed in the direction indicated by the inner logic of Feuerbach’s philosophy” Furthermore, Plekhanov criticizes Feuerbach and the French materialists of the 18th century for having a too… idealistic conception in the field of history.15

2. The tendency, which emerges from the first, to reduce historical materialism to a mechanistic economic determinism where the “objective” is always the cause of the “subjective”. For example, Kautsky insists tirelessly on the idea that “the victory of the proletariat and therewith the social revolution will not come before not only the economic but also the psychological conditions to a socialist society are present in a high degree..” What are these “psychological conditions?” According to Kautsky, “intelligence, discipline and talent for organization.” How will these conditions be created? “It is the historical task of capital” to realize them. Moral of the story: “Only when the capitalist system of production has reached a high degree of development, economic conditions allow public power to transform capitalist ownership of the means of production into social property.”16

3. The temptation to reduce dialectics to a Darwinian evolutionism, where the different stages of human history (slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism) follow one another according to an order rigorously determined by the “laws of history.” Kautsky, for example, defines Marxism as “the scientific study of the laws of the evolution of the social organism.17 In fact, Kautsky had been a Darwinist before becoming a Marxist and it was not in vain that his disciple Brill defined his method as “biological-historical materialism”…

4. An abstract conception and a naturalistic science of the “laws of history» that is strikingly illustrated by the wonderful phrase that Plekhanov uttered upon receiving the news of the October revolution: “But it is a violation of all the laws of history!”

5. A tendency to fall back on the analytical method, capturing only “distinct and separate” objects fixed in their difference: Russia – Germany, bourgeois revolution – socialist revolution, party – masses, minimum programme – maximum programme, etc.

It is well known that Kautsky and Plekhanov had carefully read and studied Hegel; but they have, so to speak, “absorbed” and “digested” it within their theoretical system, as a precursor of evolutionism or historical determinism.

To what extent do Lenin’s notes on (or about) Hegel’s Logic constitute a challenge to pre- dialectical Marxism?

1. First of all, Lenin insists on the philosophical abyss that separates “stupid” materialism, that is, “metaphysical, underdeveloped, dead, crude” from Marxist materialism, which is closer, on the other hand, to “intelligent”, that is say dialectical, idealism. Consequently, he severely criticizes Plekhanov for not having written anything about Hegel’s Great Logic, “that is, basically, about dialectics as a philosophical science”, and for having criticized Kantianism from the point of view of vulgar materialism and not “à la Hegel”. 18

2. He appropriates a dialectical understanding of causality: “Cause and effect are ergo (therefore) only moments of universal interdependence, of (universal) connection, of reciprocal sequence of events…” At the same time, he approves the dialectical approach through which Hegel dissolves the “solid and abstract opposition” of the subjective and the objective and destroys their one-sidedness.19

3. He underlines the capital difference between the vulgar evolutionary conception and the dialectical conception of development: the first, “development as reduction and increase, as repetition” is dead, poor, arid; the other, development as a unity of opposites, is the only one that “gives the key to leaps”, to the “rupture of the gradual”, to the “transformation into the opposite”, to the abolition of the old and to birth of the new.20

4. He criticizes, with Hegel, “the absolutization of the concept of law”, “its simplification, its fetishization” (and adds: “NB: for modern physics!”). He even writes that “the law, all law, is narrow, incomplete, approximate.”21

5. He sees in the category of totality, in “the displacement of the entire set of moments of reality, NB: the very essence of dialectical knowledge.”22 We see Lenin’s immediate use of this methodological principle in the pamphlet he wrote at the time, The Collapse of the Second International; he severely criticizes the apologists of “national defence” – who try to deny the imperialist character of the great war because of the “national factor” of the Serb war against Austria – by emphasizing that Marx’s dialectic “precisely prohibits isolated examination , that is, unilateral and distorted, of the object studied”.23 This is of utmost importance because, as Lukács said, the reign of the dialectical category of totality is the bearer of the revolutionary principle in science.

The isolation, fixation, separation and abstract opposition of the different moments of reality are dissolved, on the one hand, by the category of totality, and, on the other, by Lenin’s observation that “Dialectics is the teaching … why the human mind should grasp these opposites not as dead, rigid, but as living, conditional, mobile, becoming transformed into one another..” 24

Of course, what interests us here is less the study of the philosophical content of the Philosophical Notebooks. “in itself” than that of their political consequences. It is not difficult to find the common thread that leads from the methodological premises of the Notebooks to Lenin’s theses in 1917: from the category of totality to the theory of the weakest link in the imperialist chain; from the conversion of opposites to each other to the transformation of the democratic revolution into a socialist revolution; from the dialectical conception of causality to the refusal to define the character of the Russian revolution solely by Russia’s “backward economic base”; from the criticism of vulgar evolutionism to the “successive rupture” of 1917; etc. But the most important thing is purely and simply that the critical reading, the materialist reading of Hegel freed Lenin from the narrow chains of the pseudo- orthodox Marxism of the Second International, from the theoretical limits that it imposed on his thought. The study of Hegelian logic was the instrument by which Lenin cleared the theoretical path leading to the Finland station in Petrograd.

In March-April 1917, Lenin, freed from the obstacle represented by pre-dialectical Marxism, was able, under the impulse of events, to rather quickly get rid of its political corollary: the abstract and fixed principle according to which “the Russian revolution can only be bourgeois: Russia is not economically ripe for a socialist revolution.” Once this Rubicon has been crossed, he begins to study the problem from a practical, concrete and realistic angle: what are the measures that in fact constitute a transition towards socialism, that can be accepted by the majority of the people, that is, by the working and peasant masses?

The theses of April 1917

In truth, the “April theses” were born in March, more precisely between 11 and 26 March, that is, between the third and fifth Letter from Afar.

The careful analysis of these two documents (which were not published in 1917) allows us to understand the very movement of Lenin’s thought. To the crucial question: can the Russian revolution take transitional measures towards socialism? Lenin responds in two moments: in the first (Letter 3) he questions the traditional response; in the second (Letter 5) he gives a new answer.

Letter 3 contains in itself two juxtaposed moments, in an unresolved contradiction. Lenin describes certain concrete measures in the field of control of production and distribution that he considers indispensable for the progress of the revolution. First he emphasizes that these measures are not yet socialism or dictatorship of the proletariat; They do not go beyond the limits of the “revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the poor peasantry.” But he immediately adds this paradoxical phrase that clearly suggests a doubt about what he has just stated, that is, an explicit questioning of the “classical” theses: “t is not a matter of finding a theoretical classification. We would be committing a great mistake if we attempted to force the complex, urgent, rapidly developing practical tasks of the revolution into the Procrustean bed of narrowly conceived ‘theory’.”25

Fifteen days later, in the fifth Letter, the abyss is crossed, the political rupture is consummated: the measures mentioned (control of production and distribution, etc.) constitute, “In their entirety and in their development … the transition to socialism, which cannot be achieved in Russia directly, at one stroke, without transitional measures, but is quite achievable and urgently necessary as a result of such transitional measures.”26 Lenin no longer rejects a “theoretical classification” of these measures and defines them not as “democratic”, but as transitional towards socialism.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks in Petrograd remained faithful to the old model (they tried to place the Russian revolution, this unruly, untamed, unbound girl, on the “Procrustean bed of a fixed theory...” and limited themselves to a cautious wait). In Pravda of 15 March they even granted conditional support to the provisional (Cadet!) government “insofar as it fights reaction and counter-revolution”; according to the sincere testimony of the Bolshevik leader Shliapnikov, in March 1917.“ We agreed with the Mensheviks that we were passing through the period of the breakdown of feudal relations, and that in their place would appear all kinds of ‘freedoms’ proper to bourgeois relations.”27

We can understand, therefore, his surprise when the first words that Lenin, at the Finnish station in Petrograd, addressed to the crowd of workers, soldiers and sailors, were a call to fight for the socialist revolution. “You must fight for the Socialist Revolution, fight to the end, until the complete victory of the proletariat. Long live the Socialist Revolution”. 28

On the afternoon of 3 April and the next day, he presented to the party the “April theses” which, according to the Bolshevik Zalejsky, a member of the Petrograd Committee, produced the effect of a bomb explosion. Furthermore, on 8 April, this same Petrograd committee rejected Lenin’s theses by 13 votes to 2 with one abstention.29 And it must be said that the “April theses” were, to a certain extent, behind the conclusions already reached in the fifth “Letter from Afar”: they do not explicitly speak of a transition to socialism. It seems that Lenin, to the astonishment and perplexity of his comrades, was forced to partly moderate his comments. In fact, the April theses speak of a transition between the first stage of the revolution and the second “which must give power to the proletariat and the poor layers of the peasantry”, but this is not necessarily in contradiction with the traditional formula of “old Bolshevism” (except for the mention of the “poor strata” instead of the peasantry as a whole, which is, of course, very significant ), since the content of the tasks of this government (only democratic or already socialist? ) is not defined. Lenin even emphasizes that “It is not our immediate task to “introduce” socialism, but only to bring social production and the distribution of products at once under the control of the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies,”30 a flexible formula where the characterization of the content of this “control” is not determined. The only issue that, at least implicitly, involves a revision of the old Bolshevik conception is that of the Commune State as a model for the Soviet Republic, and this for two reasons:

a) the Commune was traditionally defined, in Marxist literature, as the first attempt at dictatorship of the proletariat;

b) Lenin himself had characterized the Commune as a workers’ government that wanted to carry out both a democratic revolution and a socialist revolution. For this reason Lenin, a prisoner of “old Marxism”, criticized it in 1905. For the same reason, Lenin, the revolutionary dialectician, took it as a model in 1917. The historian E.H. Carr is right. point out that Lenin’s first articles since his arrival in Petrograd “implied the transition to socialism, but stopped short of explicitly proclaiming it.”31

This explanation was to be given during the month of April, when Lenin won over the base of the Bolshevik party to his political line. It was based mainly on two axes: the revision of “old Bolshevism” and the perspective of transition to socialism. The key text on this topic is a small – little-known – pamphlet Letters on Tactics, written between 8 and 13 April, probably under the impulse of the anti-Leninist Pravda editorial of 8 April, where we find this key phrase that summarizes the historical turning point marked by Lenin and his definitive, explicit and radical break with what was obsolete in the Bolshevism “of yesteryear”: “The person who now speaks only of a ‘revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry’ is behind the times, consequently, he has in effect gone over to the petty bourgeoisie against the proletarian class struggle; that person should be consigned to the archive of ‘Bolshevik’ pre-revolutionary antiques (it may be called the archive of ‘old Bolsheviks’).”32

In this same pamphlet, Lenin, denying himself wanting to introduce socialism “immediately”, states that the Soviet power will take steps “towards socialism”. For example, “Control over a bank, the merging of all banks into one, is not yet socialism, but it is a step towards socialism.”33

In an article published on 23 April, Lenin defined the following terms to differentiate Bolsheviks from Mensheviks. While the latter are “For socialism, but it is too early to think of it or to take any immediate practical steps for its realisation” the former think “The Soviets must immediately take all possible practicable steps for its realisation.”34

What does “practically achievable measures” mean? For Lenin this means, above all, measures that can count on the support of the majority of the population. That is, not only the workers, but also the peasant masses. Lenin, freed from the theoretical limit imposed by the pre-dialectical scheme – “the transition to socialism is objectively unrealizable” – now deals with the real political-social conditions to guarantee “steps towards socialism.” Thus, in his speech at the Seventh Congress of the Bolshevik Party (24-29 April) he poses the problem in a realistic and concrete way: “What concrete measures we can suggest to the people […] We cannot be for “introducing” socialism—this would be the height of absurdity. […] The majority of the population in Russia are peasants, small farmers who can have no idea of socialism. But what objections can they have to a bank being set up in each village to enable them to improve their farming? They can say nothing against it. We must put over these practical measures to the peasants in our propaganda, and make the peasants realise that they are necessary.”35 “Introducing” socialism means, in this context, the immediate imposition of total socialization “from above”, against the will of the majority of the population. Lenin, on the other hand, aimed to obtain the support of the peasant masses for certain concrete measures, of an objectively socialist nature, adopted by the Soviet power (with workers’ hegemony).

With some nuances, this conception is surprisingly similar to the one defended since 1905 by Trotsky: “the dictatorship of the proletariat supported by the peasantry” that makes the uninterrupted transition from the democratic revolution to the socialist revolution. Therefore, it is no coincidence that Lenin was called a “Trotskyist” by the “old Bolshevik” Kamenev in April 1917… .36

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the “April Theses” represent a theoretical-political “break” with the tradition of pre-war Bolshevism. That said, it is no less true that, to the extent that Lenin had defended, since 1905, the revolutionary alliance of the proletariat and the peasantry (and the radical deepening of the revolution without the liberal bourgeoisie or even against it), the “new Bolshevism” born in April 1917, is the authentic heir and legitimate child of the “old Bolshevism.”

On the other hand, if it is undeniable that the Notebooks constitute a philosophical break with “first Leninism”, it must also be recognized that the method used in Lenin’s political writings before 1914 was much more “dialectical” than that of Plekhanov or Kautsky.

Finally, and to avoid possible misunderstandings, in no way did we want to suggest that Lenin “deduced” the April Theses from Hegel’s Logic...

These theses are the product of revolutionary realist thought in the face of a new situation: world war, and the objectively revolutionary situation that it created in Europe; the February revolution, the rapid defeat of tsarism, the massive appearance of the soviets. They are the result of what constitutes the very essence of the Leninist method: a concrete analysis of a concrete situation. The critical reading of Hegel precisely helped Lenin to free himself from an abstract and fixed theory that obstructed this concrete analysis: the pre-dialectical pseudo- orthodoxy of the Second International. It is in this sense, and only in this sense, that we can speak of the theoretical itinerary that took Lenin from the study of the Great Logic in the Berne library in September 1914, to the words of a challenge that “shook the world”, first launched on the night of 3 April 1917 at the Finland station in Petrograd.

1970

- 1Sukhanov, La Révolution Russe 1917, Stock, Paris 1965, pp. 139, 140, 142.

- 2Ibid. p. 143.

- 3Lenin, “Our Revolution (On the Memoirs of N. Sukhanov)”, Lenin’s Collected Works, 2nd English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1965, Volume 33, (p. 476-80) https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1923/jan/16.htm.

- 4Conspectus of the book The Holy Family Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th Edition, Moscow, 1976, Volume 38, pp. 19 - 51 https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1895/misc/holy-fam/holy-fam.htm

- 5A shibboleth, in Hebrew, is a phrase or word that can only be used - or pronounced - correctly by members of a group. It reveals a person's membership of a national, social, professional or other group. In other words, a shibboleth is a sign of verbal recognition.

- 6Preface to the Russian Translation of K. Kautsky’s Pamphlet: The Driving Forces and Prospects of the Russian Revolution in Lenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1965, Moscow, Volume 11, pages 408-413. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1906/dec/00b.htm

- 7ML emphasis.Two Tactics of Social-Democracy in the Democratic Revolution 6. “From what Direction is the Proletariat Threatened with the Danger of Having its Hands Tied in the Struggle Against the Inconsistent Bourgeoisie?” https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/tactics/ch06.htm.

- 8ibid.

- 9“What Can We Learn From the Resolution of the Third Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. on a Provisional Revolutionary Government?” https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/tactics/ch02.htm

- 10The only (or almost the only) exception to this iron rule was Trotsky, who had been the first to go beyond the dogma of the bourgeois-democratic character of the future Russian revolution in Results and Prospects (1906) https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1931/tpr/rp-index.htm. He was, however, politically neutralized by his organizational conciliationism.

- 11Lenin op cit https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/tactics/ch10.htm.

- 12Roger Garaudy, Lenin, P.U.F., 1969, Paris, p. 39.

- 13Garaudy, op cit, p. 40.

- 141922: “On the Significance of Militant Materialism”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/mar/12.htm. This is very topical today, when there are renewed attempts, while claiming to be Lenin, to treat old Hegel as a “dead dog”...

- 15Georgi Plekhanov 1907 Fundamental Problems of Marxism, “Marx’s epistemology stems directly from that of Feuerbach, or, if you will, it is, properly speaking, the epistemology of Feuerbach, only rendered more profound by the masterly correction brought into it by Marx.” https://www.marxists.org/archive/plekhanov/1907/fundamental-problems.htm.

- 16Karl Kautsky The Social Revolution (1902) https://www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1902/socrev/.

- 17Karl Kautsky The Agrarian Question, 1899. Plekhanov, on the other hand, had, at least in principle, criticised vulgar evolutionism, basing himself precisely on Hegel’s Science of Logic. See Fundamental Questions of Marxism https://www.marxists.org/archive/plekhanov/1907/fundamental-problems.htm.

- 18“Conspectus of Hegel's book The Science of Logic“; https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/cons-logic/index.htm. The Science of Logic, or Great Logic, was published in 1812-1816 for the first edition, 1832 for the second.

- 19Ibid.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Ibid.

- 22Ibid.

- 23The Collapse of the Second International, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1915/csi/index.htm

- 24Ibid.

- 25“Letters From Afar THIRD Letter Concerning a Proletarian Militia”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/lfafar/third.htm

- 26FIFTH Letter “The Tasks Involved in the Building of the Revolutionary Proletarian State”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/lfafar/fifth.htm.

- 27Trotsky in History of the Russian Revolution, https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/trotsky/history-of-the-russian-revolution/history-of-the-russian-revolution-trotsky.pdf p. 303

- 28G. Golikov, La Révolution d'Octobre, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1966.

- 29Trotsky History of the Russian Revolution: “The coming revolution must be only a bourgeois revolution ... That was,” says Olminsky, “an obligatory premise for every member of the party, the official opinion of the party, its continual and unchanging slogan right up to the February revolution of 1917, and even some time after.” and E.H. Carr The Bolshevik Revolution 1917-1923, Macmillan 1950, p.77.

- 30The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution [a.k.a. The April Theses] https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/apr/04.htm

- 31E.H. Carr op cit.

- 32“Is this reality covered by ‘the bourgeois-democratic revolution is not completed”? It is not. The formula is obsolete. It is no good at all. It is dead. And it is no use trying to revive it.’” Letters on Tactics, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/apr/x01.htm.

- 33Ibid.

- 34“Political Parties in Russia and the Tasks of the Proletariat”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/apr/x02.htm#s3.

- 35The Seventh (April) All-Russia Conference of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.), April 24–29, 1917, Report on the Current Situation April 24 (May 7), https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/7thconf/24c.htm#v24zz99h-228-GUESS.

- 36Cf. Trotsky, The Permanent Revolution, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1931/tpr/pr-index.htm It should not be forgotten, on the other hand, that for both Lenin and Trotsky there was an “objective limit” to socialism in Russia, insofar as an accomplished socialist society – abolition of social classes, etc. – could not be established in an isolated and backward country.